We are very proud of all of our highly rated reviews and customer feedback.

Click to read what our customers are saying!

OTHER WILDLIFE SERVICES

Having problems with larger animals? We can help out with most coyote, beaver and muskrat problems. The cost of our trapping service is a combination of time needed to set and monitor the traps, plus the cost of travel time and mileage. Anytime traps are set, with live-traps or, foot-hold traps or snares, we have to visit the traps at least once per day to take care of any captured animals and to maintain the traps in proper working order.

Both beaver and muskrats can be live-trapped in many situations, and lethal traps or snares can be used if they are causing agricultural damage or are determined to be a human health and safety problem. Relocation is an option, although a permit is required from the State of Colorado to do so. In certain locations, shooting is an option.

Coyotes are very difficult to live-trap and generally require shooting or foot-hold traps or snares to handle, both of which require a permit from the Colorado Division of Parks and Wildlife to use.

Voles have become a common pest along the northern Front Range of Colorado over the past five or six years. They have always been around, but not in large enough numbers to notice much.

There are two types of voles in our region, meadow voles and prairie voles.

Best known for the damage they cause to the base and roots of small trees and shrubs and the trails they leave in lawns, voles do their greatest damage underneath the cover of snow, when they can forage all day and night, safe from the constant threat of predators.

Where possible, we prefer to use zinc phosphide baits for the treatment of voles as the bait is both very effective and tends to be a bit safer for pets and other wildlife. However, the use of zinc phosphide is banned for residential use. It can be used on non-residential lawns as well a number of other locations including some crop land, rangeland, groves, vineyards and golf courses.

For residential use, vole control is limited to anti-coagulant baits, traps, habitat modification, exclusion and repellants. Unfortunately, all but the baits are impractical for larger areas of infestation.

Having outdoor cats in the area can help in the control effort.; howeverHowever, voles are known for their prolific breeding. With a very high mortality rate, they need to out-breed their predators. Voles will have 1 to 5 litters per year on average, but can have 10 or more litters, andin a year. Ttheir young reach maturity in a little over a month and will have their own litters.

Control efforts and cost will vary according to the property and the extent of the problem.

For larger areas, where we can use zinc phosphide, we charge by the acre

PRAIRIE DOG FUMIGATION SERVICES

3 LEVELS OF FUMIGATION SERVICES ARE OFFERED

Each active prairie dog burrow at the site is fumigated with aluminum phosphide and the burrows are sealed with paper and soil. Four to ten days after the initial fumigation, we revisit the site and re-fumigate any burrows that have been re-opened and continue to show prairie dog activity. We charge only for the burrows treated during the first visit. Burrows treated during the follow-up visit are covered by the initial charge. Further treatments later in the year will be done at the original per burrow cost. This method generally removes 92-98% of the dogs on the site.

Each active prairie dog burrow at the site is fumigated with aluminum phosphide and the burrows are sealed with paper and soil. No follow-up fumigation is scheduled and any further treatments later in the year will be done at the original per-burrow cost. This method generally removes 80-95% of the dogs on the site.

Each active prairie dog burrow at the site is fumigated with aluminum phosphide and the burrows are sealed with paper and soil. Four to ten days after the initial fumigation, we revisit the site and re-fumigate any burrows that have been re-opened and continue to show prairie dog activity. Sometime later during the year, we will re-visit the site for a second follow-up visit and fumigate any surviving animals. We charge only for the burrows treated during the first visit. Any burrows treated during the first or second follow-up visits are covered by the initial charge. This method generally removes 98-99% of the dogs on the site.

COST OF FUMIGATION SERVICES

The cost for fumigation includes both a trip charge and a charge for each burrow treated. As the trip charge covers mostly travel costs, it reflects the distance we must travel from our office near Windsor, CO. The trip charge covers each job as a whole. If multiple landowners are involved, we will split the set-up fee according to the customers’ wishes.

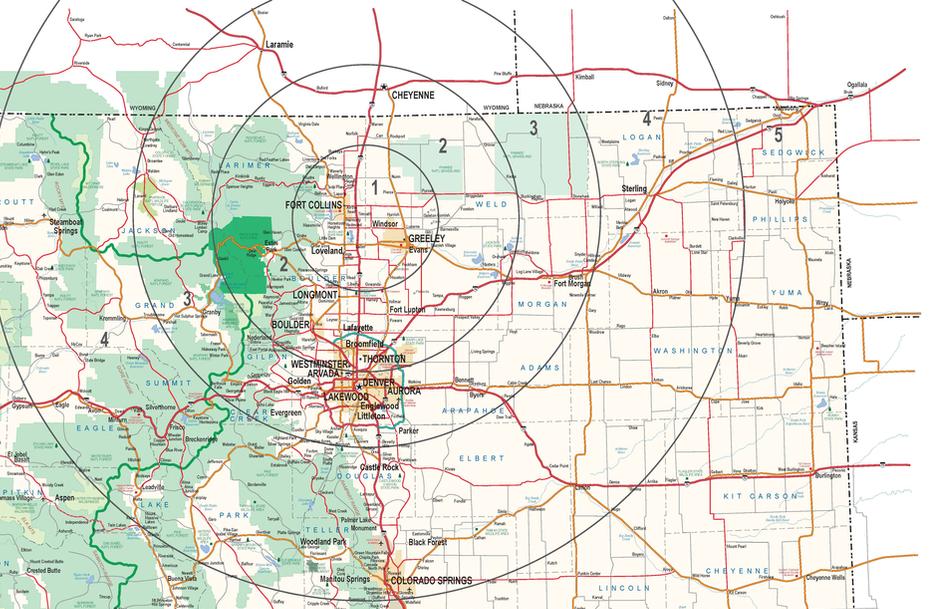

ZONE MAP

Windsor Area: $75

Zone 1: Includes Fort Collins, Loveland, Greeley, Berthoud, Wellington: $150

Zone 2: Includes Boulder, Longmont, North Denver Suburbs, Brighton, Fort Lupton, Cheyenne: $200

Zone 3: Includes Fort Morgan, Byers, Bennett, Denver, South Denver, Parker, Laramie: $250

Zone 4: Includes Castle Rock, Colorado Springs, Sterling, Kiowa, Crook, Otis, Limon, Dillon, Leadville, Vail, Eagle, Torrington: $300

Zone 5: Includes Julesburg, Holyoke, Wray, Burlington, Glenwood Springs: $350

Beyond Zone 5: The trip charge will be determined by the location of the job.

PRAIRIE DOG BAITS

The EPA currently has three baits registered for prairie dog removal: Zinc phosphide, Rozol® and Kaput-D®.

NON-LETHAL OPTIONS FOR PRAIRIE DOG CONTROL

If you are tired of the prairie dogs, but don’t yet wish to see them dead, your options are not particularly good. Live-trapping, fencing, and habitat modification can all help with pest management, but won’t often solve it.

Live Trapping

Live trapping of prairie dogs has improved greatly over the years and can now get 75 to 95percent 75-95% of the animals on the site. If well done, it is both effective and humane, but can be very expensive per animal and, unless you personally have a place in which to relocate them, the trapped dogs are usually euthanized. Most are eventually fed to the black-footed ferret recovery program or to a local raptor rehabilitation program.

If you choose to live-trap, or are forced to live-trap, take care to hire a reputable company that will get the job done. In our experience, volunteer organizations and prairie dog rescue groups rarely get the job done, or done on time. A reputable company may cost more, but you are paying for quality and expertise. They will get the job done for you.

We don’t yet offer a live-trapping service for prairie dogs but may in the future.

Barrier Fencing

Prairie dog fencing has also improved since the days of the ugly black silt fence or straw bales. Wood, concrete, metal, polyethylene tarp, electric wire, chicken wire and woven wire can all be used, possibly in combination, to construct an effective barrier. Aside from ringing (surrounding)surrounding your property with four feet of concrete, all barrier fences have their limitations and are only going to be partially effective. Prairie dogs are tenacious and mobile creatures. If they can figure a way to get around a barrier, they will do so, even if they can’t see over to the other side.

With any barrier, you will get what you pay for. A cheap and/or poorly constructed barrier is worth very little.

We do offer both fence construction and consultation. However, we generally recommend hiring a reputable fencing company for the construction. They have the proper equipment, manpower and experience to build a more attractive product for you. If interested, please give me a call and we can work onexplore some ideas.

Habitat Modification

In some very limited circumstances, habitat modification can help discourage prairie dogs from residing on your land. Plowing, seeding, dragging of mounds, removal of highly attractive land features, timing your mowing, irrigation and strategic fencing can all help make your land more or less attractive to prairie dogs. Keep in mind what habitat and features prairie dogs prefer and plan accordingly.

We can offer some suggestions if you would like.

FAQ’s

We serve customers in Colorado, southern Wyoming and western Nebraska. In much of this region, we have the most common type of prairie dog called the black-tailed prairie dog. In northwestern Colorado and some parts of Wyoming, there are also populations of white-tailed prairie dogs, and Gunnison prairie dogs.

Let us say you have a two- to three-acre prairie dog colony and often see 20 to 30 animals running around on it. Why will the bill show that one hundred burrows were treated?

Black-tailed prairie dogs can have anywhere from 10 to 150 burrows per acre of colony, with 50 burrows per acre being the average for an established colony. Therefore, a 2-acre colony may have 100 burrows, the average 10-acre prairie dog colony will have close to 500 burrows, 20 acres close to 1000 burrows, 100 acres approximately 5000 burrows, and so on. When you have many infested acres, the burrow numbers add up pretty quickly.

But I’ve never seen more than a few dogs running around. Prairie dogs also use more than one burrow. Depending on the time of year, a single prairie dog may actively use five to ten burrows and a coterie (family) of prairie dogs may be using 20 to 30 burrows. Which of those burrows do you choose to treat?

To ensure the most effective control we can offer, we fumigate any hole in the colony that may have a prairie dog in it. Not all active burrows are obvious. Depending on time of year and the weather, prairie dogs can stay down inside the burrows for over a month, allowing cobwebs to form or for snow, leaves, and other debris to cover the burrow entrance. If you fumigate only the most active and obvious burrows, more prairie dogs will survive.

Contrary to popular belief, black-tailed prairie dog burrows rarely interconnect. From experience and research, we know that less than 6% of all black-tailed prairie dog burrows have more the one entrance. In fact, it is uncommon for a single prairie dog mound to have entrances to two or more separate burrow systems. Unless you can determine differently, you have to treat each entrance as a separate system and fumigate it.

How about just treating the most active burrows? Not recommended, but we can do that, or treat just the burrows you mark. The problem with that approach lies in the percentage of effectiveness. If you miss 10 to 20% of the animals during the initial fumigation, those survivors will quickly re-open many, if not all, of the treated burrows and you will soon have the same size problem you did before the treatment.

The average black-tailed prairie dog colony has around 50 burrows per acre. If you can get a close estimate of the acreage you have, that should give you a reasonable estimate of total number of burrows. If you are uncertain of the burrow density, pick out one or more areas of the infestation that look to be representative, mark out an acre (approximately 209 feet by 209 feet) and then carefully and methodically walk the area, marking and counting the burrows as you go. Count carefully and count all potential burrows. Don’t skip burrows that don’t appear particularly active at the time.

What about a quick visual count? Be careful, not all prairie dog burrows have obvious mounds. Depending on vegetation, past disturbance to the ground, soil type and topography, half or more of the burrows may have no obvious visible mounds. If you look over a colony and visually count 20 or so burrows, double that and you should be closer to the actual number.

Once you have a good estimate on the number of burrows out there, multiply that by the appropriate per burrow fee. Add in the trip charge and you will have a pretty good estimate of the cost for fumigation.

Prairie dogs are far more active and mobile creatures than they appear. During their daily activities, they commonly range 100 or more yards from their burrows, exploring, visiting friends and family, maintaining burrows, and foraging. Prairie dogs also hit the open road.

Every spring, last year’s young are chased away from their mothers’ burrow and forced to find new homes. Some settle down on the edges of their home colony, expanding the size of that colony. Many others take to the open road, traveling many miles in any and all directions, looking for a new place to dig in. They follow roads, trails, fences, power lines, waterways, railroad tracks, and most likely the scent of other prairie dogs that have made a similar migration. Some dogs move into existing colonies and expand them. Some choose an entirely new location, dig a burrow, and wait for more prairie dogs to show up. Others find their way to an old colony that, after fumigation, now has a bunch of empty burrows.

When you begin to see prairie dogs killed on the roadways, oftentimes far from a known colony, you know the yearly migration is underway. It begins in early to mid-May and lasts until mid-October. How many prairie dogs make this trek each year? Millions.

What if your neighbors also have a prairie dog infestation and their land goes untreated, you are in for a long struggle with these pests. Any untreated prairie dogs on the other side of your fence will move back into a treated area shortly after the treatment to re-open and possibly to re-occupy some of the treated burrows.

It is always best to treat the entire prairie dog colony rather than just a portion of it. Treating only part of a colony will guarantee that prairie dogs will return and keep your land active. If possible, organize all landowners in the area to treat the prairie dog colony at once. It will save you both a little money and a lot of effort.

If you have a neighbor that can’t afford to participate, it may pay in the long term to treat the neighbor’s land. The extra expense may pay off if you can get rid of the entire colony rather than treating your portion of the colony year after year, for the foreseeable future.

In a few limited locations, putting up a barrier between the treated and untreated sides of the colony can help lessen re-infestation, but even a good barrier won’t stop the re-invasion entirely.

Part of the reasoning behind the purchase of open space lands was to protect prairie dog habitat, and so, most open space organizations are very reluctant to kill prairie dogs on their lands. Some of these same organizations are now recognizing the damage being done by unchecked prairie dog populations. The weeds and dust clouds don’t make for an attractive landscape anywhere, nor do they make the neighbors happy. In order to be a good neighbor, they may be willing to fumigate, live-trap, or put up fencing to help contain their side of a colony. Contact the open space coordinator and ask them if they are willing to help.

Many towns and cities are struggling with prairie dog problems of their own. Find out which department is responsible for the land and ask them to help control the problem. They may be willing to fumigate, trap, or fence their land. They may also be willing to allow you to treat a few burrows on their land if it is a remote or fairly small area. If you live in the City of Boulder or the County of Broomfield, you may have a much tougher path ahead. If you are on a small residential lot, less than five acres, you should be eligible for a free pro-forma permit that will allow fumigation of prairie dog burrows. If your land is larger than five acres or on commercial land, you have a much more expensive path ahead. Check with local regulations to see what is allowed.

If you have burrowing owls that nest on your prairie dog colony, the state of Colorado recommends that you not treat the area from March 15th through October 15th, or anytime burrowing owls are on site. However, fumigation is allowed during that time, and we find that burrowing owls are easy to avoid. Nesting burrows are usually obvious and easy to skip, and burrowing owls are diurnal (active during the day). They are usually out flying around during a fumigation, making them easy to avoid while fumigating.

The western burrowing owl is a state threatened species and as a migratory bird, it is illegal to knowingly kill a burrowing owl. Great care should be taken if they are present. The City of Boulder and the City and County of Broomfield require that a burrowing owl search be performed for any fumigation between March 15th and October 15th.

Burrowing owls are beautiful and intriguing birds to have around. They eat a lot of insects and small rodents without doing any lasting damage to your property. They like the prairie dog burrows for their dens and prefer the mounds for perches and the clipped grass of a prairie dog colony.

A former prairie dog colony and all of its empty burrows can be very attractive to immigrating prairie dogs. Where possible, it may help to knock the old mounds down with a scraper. Let the vegetation on the site grow tall, and let it remain that way throughout the summer and early fall months. Improving the vegetation on a treated prairie dog colony is important as a tall, thick stand of grass is the best means of discouraging prairie dogs from returning to a treated area or moving onto uninfested land. Planting the area with a cover crop may be necessary. If you must mow or graze a treated area, wait until after October 15, if you can. That gets you through the end of the yearling migration.

The Black Death can be a very frightful thing. It is deadly without timely treatment, and some forms are deadly even with treatment. However, your chances of getting plague from a prairie dog are pretty slim. 31 years of poisoning prairie dogs and no one from our crew has ever picked up plague.

Prairie dogs can get plague and carry the plague bacterium. Their fleas can then pass that bacterium onto humans or pets that are in the area, but prairie dogs don’t appear to be reservoirs for the plague, and a healthy colony does not appear to have plague in it. When plague arrives, it tends to kill out an area then disappear back into the environment.

If you live near a prairie dog colony or are on a colony during a plague outbreak, you are in danger given all of the hungry infected fleas. Get rid of the prairie dogs and the danger of plague decreases. The fumigants we use kill the fleas.

Keep an eye on your outdoor cats, they are highly susceptible to the plague. Canines don’t seem to be bothered by plague as readily as they appear to have a higher natural resistance to the bacterium. Both cats and dogs can carry and pass on infected fleas, although squirrels, and rabbits appear to be far greater risks for passing on the infection, partly due to their larger flea populations.

Plague on a prairie dog colony can actually be a blessing. If your infestation is too large to handle, or untreated colonies in your region keep re-infesting you, plague can be a great help in getting prairie dogs under control.

A prairie dog colony can be great habitat for rattlesnakes. The burrows are ideal for escaping the summer sun and winter cold, and many snakes, rattlesnakes included, den in prairie dog burrows. Prairie dog colonies also provide great habitat for mice and other small rodents the snakes feed on.

Aluminum phosphide is deadly to snakes down inside the prairie dog burrows as well as to many of their food sources. So, as is the case for most pests, if you take away the food and shelter, most of the snakes will go too.

Most of the benefits of having prairie dogs on your land are in the eye of the beholder. Black-tailed prairie dogs are interesting creatures and their colonies provide habitat for many other animals, both desirable and undesirable. Without prairie dogs and their colonies, there would be no chance of the black-footed ferret recovery. Some argue that their grazing actually improves the quality of vegetation on native grassland, although I’d argue that this only applies to native, short-grass prairie. Their grazing has no benefit to cropland.

Black-tailed prairie dogs are native to Colorado and much of the Great Plains. and They are believed to have once inhabited the entirety of the Great Plains before the arrival of white settlers, farmers, their poisons and the plague. With great effort, black-tailed prairie dogs were removed from much of their historic range; however, once the most effective and cheap poisons were outlawed for use against prairie dogs, their numbers have bounced back and they now occupy millions of acres throughout much of their historic range and number in the tens of millions of animals. Highly adaptable and tolerant of humans, they currently thrive in the Denver-metro area, all along the Front Range of Colorado and throughout the eastern plains, as well and as the eastern portion of Wyoming, Montana and New Mexico, plus the western portion of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota. Currently, the most northerly population is in Saskatchewan, Canada, and the most southern in Chihuahua, Mexico.

At this time, no. Eastern Colorado has been declared free of any native populations of black-footed ferrets, and the chance of an unknown native population still hiding out in the wild is highly unlikely.

Captive bred ferrets have been released on a number of sites throughout their historic range including recent releases near Pueblo West, north of Fort Collins, and on the Rocky Mountain Arsenal property, northeast of Denver. With the Colorado releases, these new populations are considered non-essential, and control of prairie dog colonies on land near the release sites can take place. A recent agreement by the State of Colorado allows for the incidental killing of a ferret during otherwise legal activities, including prairie dog control. It remains illegal to knowingly kill a black-footed ferret.

Were we to find sign of ferret activity on a colony, we would have to hold off on the effort until their presence could be verified. If ferrets were present, the control effort would have to stop.

With the time it takes for fumigation, it is pretty hard to hide the process from the public at large. Some smaller colonies and highly exposed infestations can be treated in the pre-dawn hours or on the weekend to reduce the chance that someone might complain. However, it takes just one complainer driving or walking by at the wrong time to create a conflict.

We do charge a fee for working in the early morning or weekend hours. The fee covers the cost of overtime and is an enticement to get us out of bed early or on the weekend.

Poisoning prairie dogs is legal and necessary in many locations. Many of the anti-control community, which is a pretty small group, are bullies and they want to intimidate you. Some of them are shakedown artists and are looking for money or time from you for the use of your private property. The more you accommodate them, the more they will ask for.

If someone is complaining, explain your situation and that your efforts are legal and as humane as possible. Live-trapping and relocation efforts are too expensive for most situations with very few places that will take prairie dogs, dead or alive. The anti’s will complain, sometimes very loudly and aggressively, but they will complain much less the next time you have to do this and are eventually likely to give up.

When fumigating, no. Neither fumigant (aluminum phosphide or carbon monoxide) should pose a risk to anyone or anything outside the treated burrows, so you don’t need to inform the neighbors. If some of your burrows are within 100 feet of a neighbor’s house or building, we need to use the safer gas cartridges as we do on your own property.

The fumigant label does require that warning signs be posted on every fumigation site. These signs will let the neighbors know that fumigation is in progress.

When using poison bait, we are not required to inform neighbors, but I would recommend doing so if any houses are near the treatment area. The poison bait is a potential threat to livestock and other wildlife, and the carcasses are a potential risk to scavengers, including dogs and cats. It is a slight risk, but better to warn them of it.

As bait applications are limited to rangeland, the potential for a risk to neighbors is very small. However, if the rangeland site is right next to a subdivision, you might wish to consider fumigation instead of bait.